The Human Factor

Setting

When B. Braun in de mid 80's started out in Asia. more precisely Malaysia, it was no more than a test case. Another medical devices company it had good contacts with (Aesculap) had already setup shop in Penang and was more than happy there. B. Braun decided that renting some space at Aesculap for one of her most labour-intensive products (surgical sutures) might just provide her with the experience wanted.

By the time I joined B. Braun in 1989, things had changed, it now occupied a new building immediately next to the similarly sized Aesculap building, employing some 2,000FTE. While both companies were doing fine, both in Asia and in general, B. Braun was the more successful one. In the middle of the 1990’s we, in Malaysia, had grown to some 5,000 – 6,000 FTE’s and had opened a new 5,000m2 administrative office about 1 kilometre down the road, next to our 2 new factories, while they were still roughly the same size. It was also around this time that B. Braun world-wide acquired Aesculap, leading to my task to do a local due-diligence and to subsequently integrate Aesculap’s Penang operations in B. Braun’s.

Challenge

The peculiarities of my task were manifold:

- Although the due-diligence had a different purpose, it would no longer make or break the deal, it should be no less involved, Yes, the take-over (although we used the preferred term: merger) was a fact, but, becoming ultimately responsible ourselves, we surely wanted to find any and all skeletons.

- While a merger always has a human factor, it was much magnified here, after-all we had started out as their little sibling, a role that we had frequently persisted in, even after we had, in truth, become the dominant of the two companies in Penang. A rather recent example was when I consulted them while introducing our pension scheme, although that did not stop me from implementing a radically different system which I considered would help reduce our churn even further (it was already well below Aesculap’s)

- I had to take a completely new look at issues like security: while our goods were bulky and of low value (especially to the outside world), theirs were small and valuable: everybody knows uses for first class scissors, scalpels, etc. of all imaginable sizes.

- Although our salary structure was, as a result of our history, not too different, my recent efficiency drive and the fact that we had to deal with a national union in addition to our in-house unions, had created quite a schism.

Solution

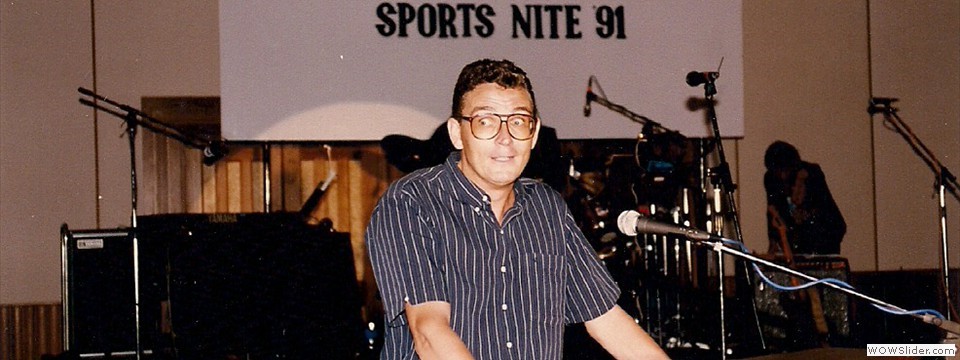

While the due-diligence ran its course as per usual, obviously finding and eliminating a number of issues; it was the Human Factor that caused problem after problem, even after the merger had become a fact and the Managing Director (MD) from Aesculap had taken his seat in our Management Board. Actually, the problem wasn’t with the expatriate top management, with all of whom I had been on a friendly foot for several years already – the MD’s wife was actually my entertainment manager in my role as Chairman Oktoberfest Penang for the Malaysian German Society –.

Senior local staff was clearly miffed that from being our mentor they now had to acquiesce in a minor, yes, maybe even, subordinate role. This frustration ran so deep that even employees that had only joined recently followed them, early manifestations were issues like:

- Refusing to move the administration into our premises

- Refusing to wear our ID-cards, persisting in using their Aescalap cards

- Not eating in our cafeteria’s

- Etc.

It wasn’t simple to ease this over; I had several trump cards however, the most important of which was that, contrary to them, I had brought our automation into the 20th century, a second was, that, in defiance of many of my German colleagues, I had made our new administration office into a full open-plan office with friendly meeting corners and such.

Our ID-cards not only replaced their old-fashioned punch cards, but also opened doors, controlled copiers, etc.. In other words: to do their job, they needed our cards but it also facilitated this job. At first they hid our card behind their ‘true’ ID, but soon it was often the other way around, after which it was only a small step to forget the old ID altogether. Obviously, their senior staff tried to enforce compliance, however there was no possible recourse as it was clearly not endorsed by top management.

The open-plan office basically caused a similar ‘revolution’, it was so much easier to cooperate; see whether some-one was busy, etc.. Soon, for most, the vast majority of their time was spent in our premises and also the senior staff found less and less reasons to pop-back to their old, now empty, offices.

All-in-all the incorporation was a great success and quickly one could hardly tell the difference between the two groups. One hurdle however, I did not manage to overcome: the pension scheme. As I explained earlier in this section, I had decided not to adapt their scheme as it, in my eyes, did little to reduce churn.

In short, with their system you only started building up a pension after 10 years with the company; once you had arrived to this point, the build-up was rapid and, assuming you had joined Aesculap early in your career, you would at retirement have built-up a very sizeable pension. Late entrants, would end up with no or a very small pension. In addition young people did certainly not take this potential pension into account when debating whether to leave and join a better paying company.

I had decided on a system that eliminated both draw-backs: everybody would start their build-up upon joining and you would get a yearly update on your pension, stipulating both what you had built-up as well as what you could take with you, should you leave our company (60%). The final pension for a ‘lifer’ however was lower than at Aesculap.

It was therefore purely natural that Aesculap ‘lifers’ preferred their pension scheme and we obviously obliged. What was surprising, and telling when it comes to peer-pressure, was that also all other Aesculap staff refused to transfer to our scheme, not just young people, who, if they truly remained with us until their retirement age would stand to gain, but even those where my calculations showed that they were always better off with our scheme as they had joined Aesculap at too late a time in their life.

Ultimately we decided not to press on; everybody received a copy of my excel file, where through complex private functions, they could play with issues like annual increase, rate of returns, date of departure, etc. they could immediately see what each plan would result in. One thing stood however: should you transfer to the B. Braun system within one year of being provided with my file, than your previous Aesculap/Braun years would be taken into consideration; afterwards counting would start from the date of acceptance.

My calculations also clearly showed that, as B. Braun, we could only loose if churn of the old-Aesculap employees would reduce to less than half our own. Should this occur, would that really be a bad thing?

See also: